Table of Contents

In a major geopolitical shift, India has suspended the 65-year-old Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) with Pakistan for the first time in its history. The suspension, which follows a deadly terrorist attack in Jammu and Kashmir, marks a critical moment in the complex relationship between two nuclear-armed neighbors. While the immediate rationale behind India’s decision is rooted in security concerns, it also signals a broader attempt to recalibrate the management of water resources in the region, amidst rising climate challenges and a changing geopolitical landscape.

This post explores the significance of the Indus Waters Treaty, its colonial-era origins, its role in South Asian geopolitics, and the emerging challenges it faces in light of modern environmental and security concerns.

The Indus River: A Lifeline and a Source of Tension

The Indus River is an ancient and vital lifeline for millions of people across India and Pakistan. Spanning nearly 2,000 miles, the river system, which includes key tributaries like the Jhelum, Chenab, and Sutlej, has supported some of the world’s earliest civilizations. The fertile lands surrounding the river have been home to the Indus Valley Civilization, and its waters continue to sustain agriculture, industry, and local communities in both nations.

However, after the British partition of India in 1947, the Indus became a flashpoint for conflict. The division of the river basin between India and Pakistan created an immediate dispute, as India gained control over the headwaters of the eastern tributaries, while Pakistan controlled the western tributaries. The stage was set for a series of water conflicts that would shape the political dynamics of the subcontinent for decades.

Colonial Legacies and the Birth of the Indus Waters Treaty

When British colonial rule ended, the legacy of imperial control over water resources became a major source of contention between the newly formed countries of India and Pakistan. The British had built extensive irrigation infrastructure in Punjab, dividing the river system in a way that left India with control over the headwaters, while Pakistan relied heavily on water from these tributaries for irrigation.

As tensions mounted between the two nations, especially after the 1947 partition, the threat of a water war loomed large. In 1960, after years of diplomatic wrangling and Cold War geopolitics, India and Pakistan, with the mediation of the World Bank, signed the Indus Waters Treaty. The treaty allocated the rivers of the Indus system between the two nations: Pakistan was given control over the western rivers—Jhelum, Chenab, and Indus—while India was allocated the eastern rivers—Sutlej, Ravi, and Beas.

Although hailed as a diplomatic success at the time, the treaty reflected a politically driven division of the region’s water resources, rather than a collaborative approach to sustainable water management. The treaty did not account for the ecological and environmental health of the river system, nor did it consider the rights of marginalized communities who depend on the river for their livelihoods.

The Strain of Modern Geopolitics and Climate Challenges

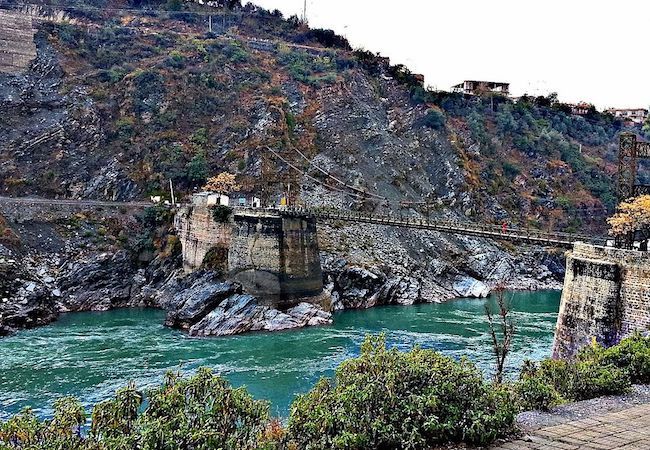

In the decades that followed the treaty’s signing, tensions over water resources between India and Pakistan have never fully dissipated. Over time, India has developed significant hydropower projects on the rivers it controls, such as the Kishenganga and Ratle projects, raising concerns in Pakistan about water diversion. Pakistan has taken legal action against India, but India has increasingly dismissed these concerns, citing the need to meet its growing water demands and energy needs.

The situation has only worsened as climate change, population growth, and shifting economic priorities exacerbate water scarcity in both countries. India is facing an unprecedented water crisis, with projections indicating that by 2030, water demand will far outstrip available supply. Similarly, Pakistan, already heavily reliant on the Indus system, is also confronting severe water shortages, which threaten agricultural productivity and food security.

Climate change is amplifying these challenges. Rising temperatures and erratic rainfall patterns have already begun to disrupt water cycles across the region. The melting of glaciers in the Himalayas, which feed the Indus River, poses a long-term threat to the river’s flow. In addition, the construction of upstream hydropower projects in countries like China and Nepal adds further pressure on the shared river system.

India’s Strategic Shift: Hydro-Hegemony and the Suspension of the Treaty

India’s decision to suspend the IWT should not be seen as a complete withdrawal from the agreement but rather as a strategic maneuver to assert greater control over the Indus River system. India’s leadership, particularly under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has increasingly linked the treaty to national security concerns. The 2016 Uri attack, in which 19 Indian soldiers were killed by militants allegedly based in Pakistan, was a key moment in shifting the political narrative around the treaty. Modi threatened to abrogate the treaty, and the idea of revising the terms of the IWT gained traction within Indian political circles.

With India facing growing internal water demands, as well as increasing geopolitical competition in the region, the suspension of the treaty can be seen as an attempt to consolidate India’s position as the upper riparian state and strengthen its control over the region’s water resources. India’s investments in large hydropower projects along the Indus River, including the Kishenganga and Ratle projects, are seen as part of a broader strategy to bolster India’s hydro-hegemony over the shared river system.

Pakistan’s Limited Options

For Pakistan, the suspension of the IWT is a serious blow, as the country’s economy and agriculture are heavily dependent on the Indus River system. As the lower riparian state, Pakistan has long relied on the flows of the western rivers allocated to it under the treaty. However, with India increasingly disregarding the treaty’s provisions and asserting greater control over the river, Pakistan’s options are limited.

Pakistan can legally contest India’s actions under the treaty’s dispute resolution mechanisms, including arbitration by the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA). However, India’s recent rejection of the PCA’s ruling on the Kishenganga and Ratle projects signals a growing indifference to international legal processes. Pakistan, already facing a mounting water crisis, has few diplomatic tools to compel India to abide by the treaty’s terms.

A New Era of Water Diplomacy?

The suspension of the IWT presents a critical juncture for India, Pakistan, and the global community. While the treaty’s suspension could exacerbate tensions between the two nations, it also provides an opportunity to reassess the region’s transboundary water governance principles. The realities of climate change, population growth, and the evolving geopolitical dynamics of South Asia are now challenging the colonial legacies that shaped the treaty’s framework.

Rather than focusing on political control over water, India and Pakistan must work together to develop a more collaborative, sustainable, and ecologically responsible approach to managing the Indus River system. The future of water security in the region depends not only on diplomacy but also on addressing the fundamental challenges of climate change, resource distribution, and the rights of marginalized communities.

Conclusion: Moving Beyond Colonial Legacies

The suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty marks the end of an era. It reflects both the enduring geopolitical tensions between India and Pakistan and the urgent need to rethink how shared water resources are managed in the face of changing environmental conditions. Moving forward, the world must focus on building a water governance framework that emphasizes cooperation over competition, ecological sustainability over control, and the rights of communities over nationalistic agendas.

Author Profile

- Syed Tahir Abbas is a Master's student at Southwest University, Chongqing, specializing in international relations and sustainable development. His research focuses on U.S.-China diplomacy, global geopolitics, and the role of education in shaping international policies. Syed has contributed to academic discussions on political dynamics, economic growth, and sustainable energy, aiming to offer fresh insights into global affairs.

Latest entries

GeopoliticsAugust 23, 2025Previewing the White House Visit of South Korean President Lee Jae Myung

GeopoliticsAugust 23, 2025Previewing the White House Visit of South Korean President Lee Jae Myung Middle East ConflictJuly 22, 2025Israel’s Deadly Attacks on Gaza: A Dire Humanitarian Crisis and International Calls for a Truce

Middle East ConflictJuly 22, 2025Israel’s Deadly Attacks on Gaza: A Dire Humanitarian Crisis and International Calls for a Truce Middle East & North AfricaJuly 20, 2025Israel Targets Damascus Amid Rising Tensions in Syria

Middle East & North AfricaJuly 20, 2025Israel Targets Damascus Amid Rising Tensions in Syria Middle East AffairsJuly 14, 2025An Open Letter from Gaza’s University Presidents: Resisting Scholasticide Through Education

Middle East AffairsJuly 14, 2025An Open Letter from Gaza’s University Presidents: Resisting Scholasticide Through Education

2 comments

India wouldn’t dare to suspend this they just threaten so far but there ain’t physical action commenced so far and in order to be of UN India wouldn’t break like this.

This blog is a gem! Your unique perspective and writing style make each post a joy to read. You have a real talent for drawing readers in. Keep up the incredible work and keep sharing your wonderful thoughts with us! 🌟